Wetlands are powerhouses of biodiversity, supporting endless lifeforms. We show you how (and why you should) build a wetland.

It is possible to create extraordinarily beautiful and meaningful habitat by building a wetland.

Unlike a typical dam, a wetland will have been designed to allow for a broad range of aquatic plants, creating homes for frogs, insects, visiting birds, dragonflies, bats, antechinus, planigale, brolgas, native geese and bandicoots, to name a few.

Wetlands, swamps, damplands and sumplands all vary in terms of the amount of water they hold at different times of the year. With some holding water most of the time and others only showing water above soil during very wet seasonal rains.

They are all extremely important, as they provide homes and drinking water for our exceedingly beautiful wildlife and help to cool local microclimates. They are dynamic vibrantly rich habitats, which allow us to reconnect with the wild and welcome in an exciting chorus of animals.

Wetlands and clay soil

The first step to designing and beginning to build a wetland is to identify your soil type, as only clay will do. And not just any clay. Some clay soils are dispersive meaning that they do not stick together when wet.

A clay soil that when moist “can be rolled to the thickness of a pencil without breaking apart, will hold water once it has been compacted” (Romanowski 1998).

Another approach for determining the clay content of your soil is to place a sample of soil taken from the desired wetland site and place it in a glass jar. Shake the jar vigorously with lid tightly on and then let the soil settle for up to 24 hours, by which time sand should settle to the very bottom. Followed by silt and clay. Click here for help.

To test if soil is dispersive (structurally unstable) click here.

Where to place and build a wetland

Your site will often give you clues as to the lowest position on your block to place a wetland, as the plants present in wet and boggy areas will often be different to those found on the rest of the block.

A property survey with an experienced surveyor will help to formalise the best site, as well as discussions with an experienced earth worker who specialises in building wetlands/dams.

It is very important to use contractors that have extensive experience building or overseeing wetland construction to ensure water storage is achieved. The lowest point on your property is often the best place to place a wetland, but there might be factors that limit its access.

Or in some cases, factors that compromise its structural integrity such as too much run off, in which case an alternative location needs to be found.

How to size your wetland and its use

The sizing of the wetland is completely dependent on the size of your block, your budget, catchment area, its use and any rules or permit requirements stipulated by water authorities or local government.

For example, Agriculture Victoria stipulate that… “If you are planning to build a wetland for irrigation (or other commercial purposes), you need a licence to take and use water. Dams used for domestic and stock purposes do not require a licence, up to a certain size” Consult your states’ water authority for details relevant to your area.

With regards to its catchment area, a very large dam with a very small catchment area may not fill. So it pays to play around with numbers a little.

There is an excellent formula on the Agriculture Victoria website which helps you to calculate your catchment area potential. The formula can be used across all states as long as adjustments are made to take into account the Location Factor. You will see what is meant by this once you visit the site.

Wetland design

The focus here is on wetland design that prioritises biodiversity values, therefore the ideal wetland is one that allows for maximum biodiversity values to be expressed.

This is best achieved when the wetland allows for a broad mixture of plants to be established both on the edges and inside the wetland itself, via a relatively shallow gradient transition.

While certain areas of the wetland can be designed to be deep, it is important that the edges allow for a variety of plants – both those that require shallow water levels and those best suited to deeper water to establish – to create high shoreline complexity.

For example. Maundia triglochinoides, found in south-eastern Queensland grows in waters up to 50cm deep, while Craspedia species like seasonally wet areas and do not thrive in permanent water.

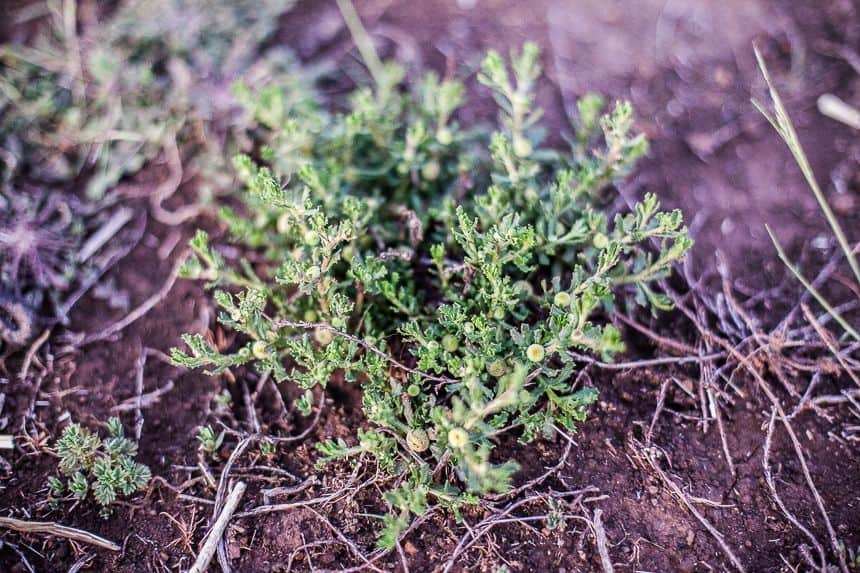

Wetland plants

Each state will have aquatic plants indigenous to its area. It is therefore wise to research what those plants are and find a local nursery that specialises in aquatic indigenous wetland plants.

Alternatively, look out for someone who has wetland plants on their property. If you are able to identify them and ensure that no weed plants are present at their site, then transplanting wetland plants from one wetland/dam to another is extremely easy to do.

Alisma plantago-aquatica is commonly found in many states and has very small pale pink to white flowers. Hydrocotyle verticillate sits just above the water’s surface with its pretty round leaves marked by shallow rounded teeth, not to be confused with the invasive Hydrocotyle ranunculoides which is a serious weed in Western Australia.

Billy Buttons such as Craspedia paludicola have distinct yellow heads that stand tall and vibrant in the sun in seasonally wet soil. Sedges such as Baumea arthrophylla and Baumea rubiginosa are commonly planted on the wetland fringe and shallow waters edge.

Plants in the genus Bolboschoenus, Carex and Chorizandra, Cladium, and Cyperus all include sedges that form habitat of great importance for many animals. Plants in the family Goodeniaceae, which includes Gunnera cordifolia a Tasmanian species. Haloragis brownie “Swamp raspwort” a sprawling herb and species in the genus Myriophyllum can add great diversity.

The family Juncaceae, the rushes, grow in seasonally wet or waterlogged soils with the tallest species standing five metres in stem length. The family Juncaginaceae include the tuberous-rooted species Triglochin, whose roots are a traditional food in Australia.

The plants listed here are but a tiny sample of many described in the book ‘Aquatic and Wetland Plants: A Field Guide for Non-tropical Australia’ by Nick Romanowski (CSIRO Publishing, 1998).

How to use your wetland

A well-designed wetland is a thing of great beauty. A heavenly paradise of biodiversity and orchestral singing: birds, frogs, dragonflies, visiting ducks and swans, brolgas, depending on where you live.

Think of it as the most amazing natural swimming pool, where all the indigenous plants you have introduced filter and absorb nutrients. In summer the wind passes through the water’s surface cooling down local microclimates through evapotranspiration.

The trees on its perimeter provide shade and create a perfect place to read a book or to take a snooze. Snakes will be drawn to it too, but once you learn to live with them you will find the pleasure of the wetland far outweighs any fears.

Wetlands once thrived in all states of Australia, but many have been drained during colonisation to make way for development.

Wetlands, waterholes, sumplands, swamps, damplands are powerhouses of biodiversity, they support endless lifeforms.

They are the taps, showers, loungerooms, kitchens and restaurants of the animal world and for us they are beautiful places filled with the theatre of the wild. By reintroducing wetlands to our landscape we are reintroducing life itself.

Images: Village Dreaming